Saracens - the best team in England?

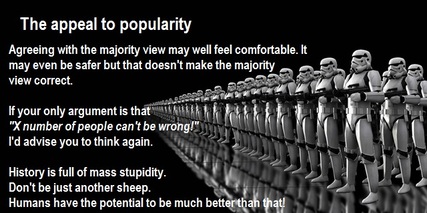

Saracens - the best team in England? An assertion is a positive statement that lacks support or reasons. We make them all the time in everyday life and most of the time they cause no problem; “The Earth is round”; “Light travels faster than sound”; “Saracens are the best Rugby team in England”. These statements are widely accepted (especially the last one in my household!) and so don’t require us to offer any evidence to support them. Indeed, life would be rather tedious if we had to justify such statements every time we made them.

In the last 100 years many philosophers have developed ideas around where the “burden of proof” lies and have generally concluded that it always lies with the person making the claim. One famous example of such a philosopher is Bertrand Russell and his celestial teapot. This is an analogy which tries to demonstrate why the philosophic burden of proof is always with those making the claim, rather than shifting it onto those who would dispute the claim.

Russell claims that this is what religious people have a tendency to do; to say that the sceptic has a duty to prove the theist wrong. To show the absurdity of this Russell said that if he claimed that there was a teapot orbiting the Sun, somewhere between the Earth and Mars, it is nonsensical to expect others to believe him on the grounds that they cannot prove him wrong.

Many orthodox people speak as though it were the business of sceptics to disprove received dogmas rather than of dogmatists to prove them. This is, of course, a mistake. If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is an intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense. If, however, the existence of such a teapot were affirmed in ancient books, taught as the sacred truth every Sunday, and instilled into the minds of children at school, hesitation to believe in its existence would become a mark of eccentricity and entitle the doubter to the attentions of the psychiatrist in an enlightened age or of the Inquisitor in an earlier time. (Russell, 1952) |

Have I made any assertions in this post?

References:

Russell, Bertrand. "Is There a God? [1952]" (PDF). The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, Vol. 11: Last Philosophical Testament, 1943–68. Routledge. pp. 547–548. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed