It is the start of term and so I wanted to focus on a word which is essentially to do with learning and knowledge. When students enter the Religious Studies classroom they often have preconceived ideas about a topic – they may already have made their mind up that God does not exist or that Jesus is the saviour of the world. As a teacher it is my job to challenge these preconceptions and get pupils thinking critically. By “critically” I do not mean purely negatively or pessimistically; looking to shoot down the views of others and pick holes for the sake of it. By “critically” I mean a mindset of questioning the views of others, testing ideas out and asking further and deeper questions. In this sense I want my students to try and be agnostic – which literally means without knowledge. Agnostic in the sense that they may not yet know the ultimate truth and concede that they may never know the truth, but that does not mean that they give up seeking. They are active and critical in lessons and seek the truth for themselves. Crucially they don’t just accept the taboos and norms of society at face value and find out for themselves. So if you are starting at a new school this week (like me!) or just beginning a new academic year - try to be agnostic and seek for yourself.

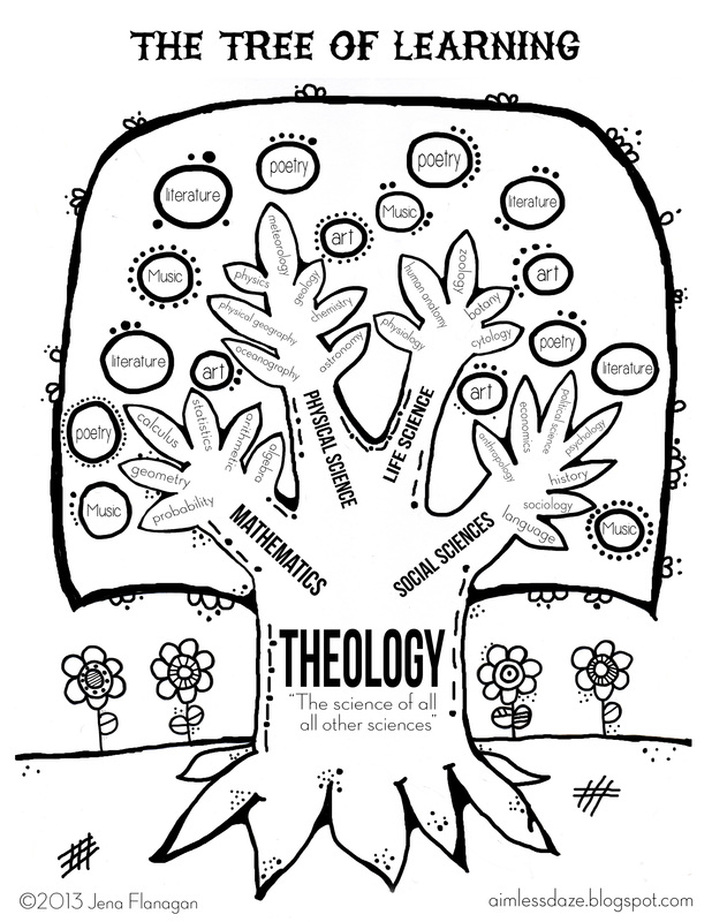

A colleague passed me this article from the i newspaper and it is worthwhile reading for any young person studying RS (or their worried parents!) and considering what course to read at university. A lot of students I teach have a rather limited view of where Theology can lead you; most think you can only be a priest or a teacher! I have to assure them this is not the case and that Theology (as well and Philosophy or Religious Studies) is a great launch pad into a huge number of careers.

The Result?

Kate Rowe writes; “This evolution of the subject can lead to careers in law, youth work, teaching, social work, lobbying, politics, the arts, business and senior management; and applies the meta-physical to the everyday”. So if you like RS, but worry what you would do in the long-run – don’t! You will be a great critical thinker, highly empathetic, skilled at rhetoric, and highly employable!  The Ethical belief that there are absolute standards against which moral questions can be judged, and that certain actions are right or wrong, regardless of the context of the act.  Absolutists are those people who think that moral laws apply equally to all people at all times, and in all places. The goodness or rightness of an action is not dependent upon the outcome or what was intended to happen; only the act itself. So an Absolutist would say that stealing is always immoral, regardless or whether you are trying to feed your starving family, killing can never be justified and adultery is always forbidden. Even if goodness does come about from your action it is still not justified.  This view is accompanied by a belief that there is an absolute standard by which all ethical actions can be judged; these range from God as lawgiver (Natural Law, Divine Command Theory), logical duty (Kant’s Categorical Imperative) or the Form of an ethical principle such as Justice, Truth or Good (Plato). At first glance this seems pretty straightforward and a great way to do Ethics - we all know where we stand on an issue, we would know how others were going to act and judgements on morality would be totally clear cut. This allows us to write documents such as the declaration on human rights and to judge evil dictators who cause atrocities to their peoples. Simple...  But of course things are never that easy! All absolutist theories are variously criticised because of where they believe their moral absolutes come from - the existence of God cannot be proved beyond doubt; Kant’s logic is flawed; the Forms are illogical. A more general criticism is that absolutism does not respect diversity of cultures and different traditions. Why is my world-view more likely to be correct that another? For me the most pertinent problem with Absolutism is that life is not that simple. Kant drew attention to this such problem himself in Critique of pure reason; what if a crazed axe-murderer came to your front door and asked you where your father is? You could lie – many would say you should lie – but imagine if everyone in the entire world lied all the time. If everyone lied, there would be no “telling the truth” and, thus, no real lying. As the law is logically contradictory, you have a perfect duty not to lie. You have to tell the axe-murderer the truth, so he can go and kill your father. How can this be right? It’s in situations like this that strict ethical systems with specific decision procedures tend to fall apart. Morality is simply too complex and too full of exceptions for these theories to ever fully work.  Henry Ford Henry Ford The new L6th were set the task of reading Brave New World over the Summer Holiday - and so I did too! This post is no substitute for them reading the books themselves (!), but I hope it provides a useful summary and gives some useful questions to consider and discuss. Synopsis: The book is set in the year in the year of Our Ford 632; 632 years after Henry Ford created the first mass produced car, the Model T, and so became the deity of humanity. The novel describes a community based on the principles “community, identity and stability” in which families have been eliminated and citizens are both physiologically and psychologically conditioned to accept their position in society with pleasure. They are born in hatcheries into a pre-determined caste system and all children are educated using the “hypnopaedic process”, a system which provides each child with subconscious messages to mold the child’s lifelong self-image and social outlook. Citizens are encouraged to value consumption with platitudes such as “ending is better than mending” and as a result employment is near 100%. People are given the drug Soma, a relaxant and hallucinogen which sends people on “holidays” from the discomforts of life. Rather than have families, casual sex is encouraged and monogamy or celibacy is anathema. The story focuses on Bernard Marx, an Alpha+ who travels to an area of “savages” and discovers the illegitimate son of a high ranking official. He bring the man, John, back to civilisation. Eventually John ends up in front of Mustapha Mond, the Resident World Controller of Western Europe. They debate the merits and shortcomings of the new world state and the relative value of primitivism. John is eventually retreats to a solitary lighthouse but ultimately nothing can prevent the eventual corruption and self-destruction of John the Savage. History The work was published in 1932 in the wake of World War One, but before the totalitarianism of Nazi Germany and the Soviet union that inspired another dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four. It was highly influenced by the discoveries of behaviourists and psychologists such as Watson, Skinner and Freud. It also came before the discovery of DNA and so focuses on the mind and physiology and not genetics as the way that society orders it citizens. Aldous Huxley wrote the book as an antidote to H. G. Wells’ utopian novels Modern Utopia (1905) and Men like Gods (1923). Wells wrote books which highlighted the positive future possibilities for mankind, whilst Huxley provides a frightening vision of the future.  Themes you might consider exploring:

Questions to discuss:

Suggested further reading:

Reasoning or knowledge which proceeds from theoretical deduction rather than from observation or experience.  This post follows on from Syllogisms two weeks ago - logical systems by which philosophers try to build coherent arguments. "A Priori" reasoning is any form thinking which relies upon the meaning/definitions of words rather than observations about the world. A Priori knowledge is independent of experience. Galen Strawson describes A Priori reasoning as an idea “that you can see that is true just lying on your couch. You don’t have to get up off your couch and go outside and examine the way things are in the physical world. You don’t have to do any science.” (Sommers) Examples include “all bachelors are unmarried men” and not “all bachelors are happy”. The obvious advantage of this kind of thinking is that everyone must agree with you because what you are saying is self-evident. There is only one major example of this type of argument in relation to the existence of God and that is the Ontological argument - that we know God exists because existence is part of his being (ontos). It was first formulated by St Anselm in the 11th Century in his Proslogion. In this work he argued that, as God is the greatest being that can be conceived and existence in reality is greater than existence only in the mind alone, God must exist in reality.

The Ontological argument, although revived from time to time by various scholars (including Descartes and recent versions by Hartshorne, Plantinga and Malcolm) has never been hugely popular because it is not a very convincing way of proving God - people tend to prefer to base their reasoning on our experience of the world and this is why other arguments such as the Teleological and Cosmological have been more popular since the time of Aquinas.  1. A misleading, deceptive or false notion. 2. An argument that uses poor reasoning. Over the course of the year there will be a number of types of fallacies presented as “word of the week” such as Straw Man, Ad Hominem and Tu Quoque. For now it is enough to outline what this word means in general. In common usage the term can mean any idea which is false or misleading such as “That the world is flat was at one time a popular fallacy”. In Philosophy and Ethics we are more interested in the second use of the term; an argument that uses poor reasoning. Last week the word of the week was Syllogism (see here). Sometimes Syllogisms that look good prove to be false; these are known as deductive fallacies. This looks like a good syllogism at first glance - but it is in fact fallacious. “That creature” may well be a pig, but the conclusion does not follow from the premises. In fact it could be a shrew, aardvark, or even a crocodile. The problem is that statement 1 has been reversed; in this case “all pigs have snouts” is being read as “all snouted animals are pigs”. It is a common misconception that the only snouted animals are pigs, and so at first glance the syllogism works. But when you think about it more carefully you see that it is an example a deductive fallacy; individually the steps appear logical, but when placed together is actually incorrect  The news this week of Baby Gammy, a child born with Down’s Syndrome to a surrogate mother in Thailand and allegedly rejected by his intended parents in Australia (whilst they did adopt his healthy twin sister - http://bbc.in/1lwdFaA), has brought into public focus the complex issues that Surrogacy can raise. As ever, I am not trying to give my opinion or offer any answers - I just want to raise the questions. What is surrogacy?  Surrogacy is an arrangement whereby another woman carries and gives birth to a baby for a couple who want to have a child. There can be a number of reasons for making such an arrangement such as repeated miscarriages or a malformed/absent womb. There are a two main ways that surrogacy can work:

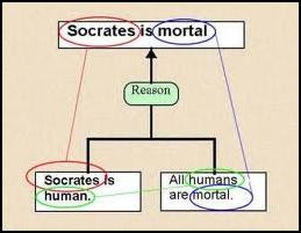

After the birth of the child it is common practice for the baby to be adopted formally by the couple so that they gain legal standing as the child’s parents. Surrogacy for profit is not legal in the UK (or Australia), although you can do it altruistically and receive expenses from the couple who wish to have a baby. This regulation has led many couples to go abroad to countries where the law is different (such as the USA and Thailand). What are the issues?  As seen in the case of baby Gammy, there is the risk of the couple pulling out of the arrangement for one reason or another; they get cold feet; they split up; they become ill or die. This would leave the surrogate in a very difficult position having given birth to a child that may not even be genetically hers. Who will have ultimate responsibility for the child? On the flip side, the surrogate may want to keep the baby and not allow it to be adopted by the couple - this can be mitigated against by having a very clear contract drawn up in advance, however this would not negate the emotional turmoil a surrogate mother might go through. The couple may want to have the baby aborted if they discover that it has a disease such as Down’s or Spina Bifida - do they have the right to force the surrogate to undergo the procedure? Is the unborn foetus essentially their property if they have signed contracts and contributed their own genetic material? This leads us to consider whether we want to have the unborn commercialised at all - can a price be realistically be put on a human life? Is it ethical for a relatively wealthy couple to travel to a less developed nation (as in the Baby Gammy case) to seek a surrogate? Is this a form of human exploitation? Or should we accept that we live in a global environment and this extends to having a child? As the child grows up, do they have a right to be able to contact the surrogate mother, especially if it was a traditional surrogacy and they have the Surrogate’s genes? Does the surrogate mother have the right to contact the child? Many will have assumed until now that the “couple” are heterosexual, a man and a woman. What if they are gay or lesbian? Should they be allowed to have a surrogate child? Given that they are allowed to marry in the UK could they be stopped from having a child in this way? Finally, we might consider if couples have a moral prerogative to adopt children that are already alive and unwanted, rather than creating a whole new life. The urge to have a child that is genetically related to you is a very strong one, but is it more ethical to adopt existing children?  These are just a few of the issues - I am sure that many of them will be discussed in tomorrow's Moral Maze on BBC R4 at 20.00 BST. (http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04cffpz)  A formal argument in logic that is formed by two statements and a conclusion which must be true if the two statements are true. Last week Richard Dawkins got in trouble on twitter for trying to show how one type of syllogism works (https://richarddawkins.net/2014/07/response-to-a-bizarre-twitter-storm/). I don’t want to get into whether he was right for saying what he did - but it was interesting that a lot of people criticising him missed the whole point of his original tweet - to demonstrate the power of the syllogism! So what is this form of logical reasoning and why is it useful to philosophers? At its most simple a syllogism is two statements that relate to one another and lead to a logical conclusion. A basic example is: The beauty of a good syllogism is that the conclusion must be indisputable if the statements are correct. Most A-level students first come across syllogisms when they study the Ontological argument. Anselm, when he wrote Proslogion he lays out his argument in chapter 2 in a fairly verbose way:

Quite complicated! However, it can neatly be summed up in this syllogism:

Now, having simplified the argument into a syllogism, we can then go on to test and discuss the logic and the reasoning more easily - this is why they are so useful!

|

Archives

June 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed